February’s History Friday: Kraus-Anderson Rebuilds the Minneapolis Mill District

By Matt Goff, Kraus-Anderson Historian/Archivist

There’s nothing more central to the history of Minneapolis than the mills along St. Anthony Falls. When soldiers were building Fort Snelling, they constructed a government mill next to the falls to saw lumber for the fort’s construction. Once they finished the fort, the mill produced flour to feed the people stationed there.

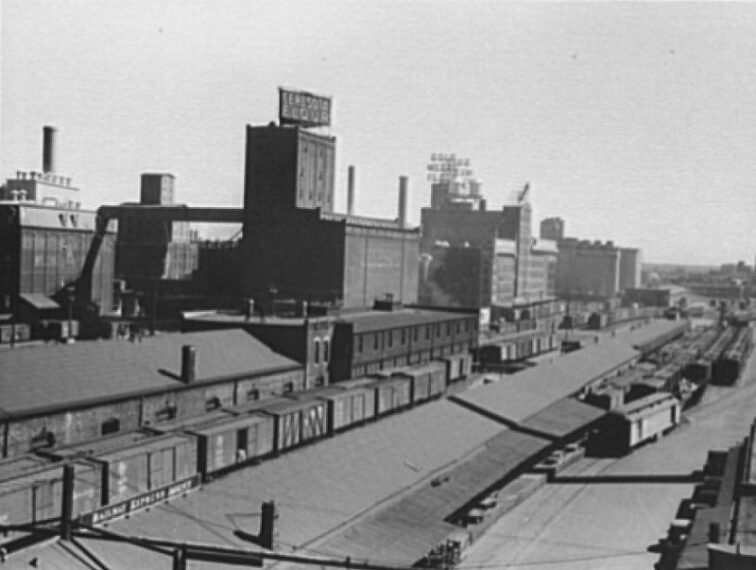

The same pattern was followed for the private mills. The first mills provided lumber for the houses and buildings of Minneapolis, St. Paul, and the whole region. The next generation of mills made flour that was shipped all over the world. For the fifty years between 1880 and 1930, St. Anthony Falls provided the energy for a district that contained more than twenty mills, dominating the U.S. wheat processing industry. By the 1980s, the few mills that survived had been shuttered for half of a century. Kraus-Anderson was chosen to restore these mills and give them a second life. Ironically, the second life that Kraus-Anderson gave these buildings will probably last longer than the industry that started Minneapolis.

Ceresota Building

In 1987, Kraus-Anderson renovated Elevator A, which is now called the Ceresota Building. A rare example of a brick grain elevator in the Twin Cities, it has been on the National Register of Historic Places since the early 1970s. The Ceresota Flour mural on the south wall of the building is a distinctive feature that many considered worthy of preservation. However, this huge windowless wall posed a challenge for the project’s designers. The architects at the storied firm of Ellerbe Becket (gone but not forgotten) proposed a solution that won praise from contemporary critics. The space inside this part of the building is focused on an interior atrium, and the windowless wall is clad in mirrors, making the atrium appear much larger than it is. A semicircular granite fountain butts up to the mirror, making the fountain appear to be a full circle and reinforcing the illusion created by the reflective wall. The renovated Ceresota Building was initially used as an office building, but the senior living facility that now occupies this landmark maintains these key elements of the renovation.

Northstar Mill

From 1998 through 1999, Kraus-Anderson converted the North Star Woolen Mill into the North Star Lofts. Also included in the National Register of Historic Places, the North Star Woolen Mill represents an interesting chapter in the history of Minneapolis’ milling district.Best known for producing flour, the mills along St. Anthony Falls were sometimes put to other uses. When W.W. Eastman and Paris Gibson developed the cataract mill on the west side of the Mississippi, they imagined that Minneapolis could be, like Lowell, Massachusetts, a water-powered textile center.

This dream never really materialized, but the North Star Woolen Company, focusing on quality wool products, was a successful venture while it lasted. In the 1920s, it was the nation’s largest producer of wool blankets. By the middle of the 20th century, the company moved, and the structures that housed it were put to other uses. The buildings that exist today were put up between 1890 and 1939. The solid industrial construction, enclosing large spaces with high ceilings and exposed masonry, along with its proximity to downtown Minneapolis, made the North Star ideal for conversion into lofts. In 2015, the residents of the North Star Lofts put a finishing touch on the project when they restored the North Star Blankets sign that towers over the historic complex.

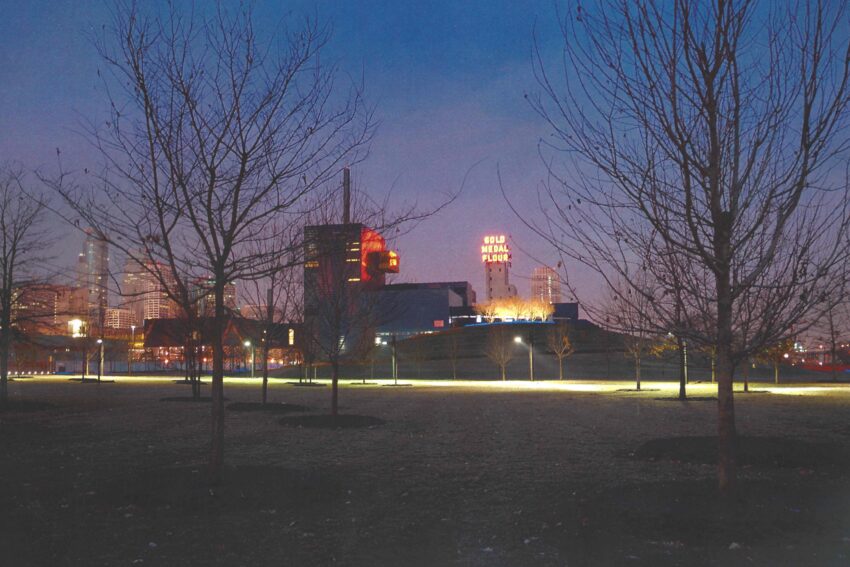

Gold Medal Park

The last major project that Kraus-Anderson undertook in the Mill District was something of a crowning achievement. In 2006, Kraus-Anderson served as a general contractor for Gold Medal Park.

Building a park might not be a typical project for Kraus-Anderson, but Gold Medal is not a typical park. It was a collaboration among the Guthrie Theater, the city of Minneapolis, and, crucially, the McGuire family. In 2006, the Guthrie Theater relocated to the southeast edge of downtown, near the old mills. William McGuire, who made a fortune as the chief executive of United Health, leased seven acres of land adjacent to the new theater to create an innovative public space.

Excepting the belt of grass that followed West River Parkway into downtown in the 1990s, Gold Medal Park was the first substantial green space added to downtown Minneapolis since the Loring and Elliot Parks were laid out in the 1880s. Creating this new place involved more than just planting trees. A century of industrial use left the soil contaminated. Landscape architect Tom Oslund turned this challenge into the park’s centerpiece. The polluted soil was piled up and covered with a barrier of clean earth. This central mound, approached by a swirling path, is both a focal point and a viewing station. The Gold Medal Park Conservancy now operates the park.

Kraus-Anderson was a key partner in the redevelopment of the Minneapolis Mill District, working on most of the major projects that made this success story happen.

CATEGORY: History