November’s History Friday: Kraus-Anderson and Minneapolis’ Iron Age

By Matt Goff, Kraus-Anderson Historian/Archivist

As a construction and real estate company with a portfolio that dates back more than 125 years, the history of Kraus-Anderson can stand as a proxy for the economic history of Minneapolis. Between the years 1907 and 1917, Kraus-Anderson worked on three projects that are emblematic of Minneapolis’ industrial age.

J.L. Robinson, Kraus-Anderson’s founder, completed a few significant projects early in his career. The Dayton Building (1901) and the Deere and Webber (1902), for instance, were both completed in the first years of the 1900s. These early successes were important for Robinson’s career, and to the history of Kraus-Anderson, but it was what he did next that cemented his reputation as a builder.

Beginning in 1907, and continuing for a decade, Robinson took on projects that laid the foundation for the heavy industry of Minneapolis. This was a time when rail was crucial transportation technology. The big industrial plants were located along railroads. The warehouse district, just north of downtown, was a transportation hub. In 1917, Robinson built the Iron Store in this neighborhood.

Northeast Minneapolis was and still is, crisscrossed by railroads. Northeast is the part of Minneapolis where, today, you are most likely to find the sort of heavy industrial plants that once covered Minneapolis. It’s the same part of the city where Robinson constructed the Crown Iron Works industrial campus.

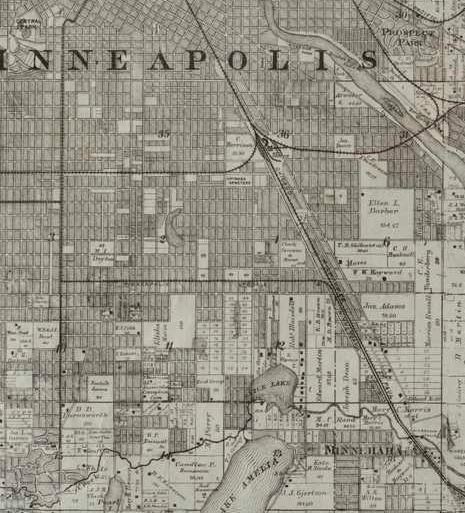

The third major hub of industry ran along the Hiawatha corridor that cuts a diagonal line through south Minneapolis. This corridor is arguably the oldest road in Minnesota. It is certainly Minnesota’s first military road, built to facilitate travel between the government mill at St. Anthony Falls and Fort Snelling. Before Minnesota became a state, the territorial government commissioned a railroad to run along this line, past Fort Snelling, and on to points south, connecting downtown Minneapolis with the wider world.

Sometimes called the Milwaukee Road (because the word “Milwaukee” was a constant amid the railroad’s name changes), and known to contemporaries as “hell’s half-acre,” the Hiawatha corridor was home to some of Minneapolis’ heaviest industry, and this is where Robinson began building the industrial buildings that would fill his workday for the next ten years.

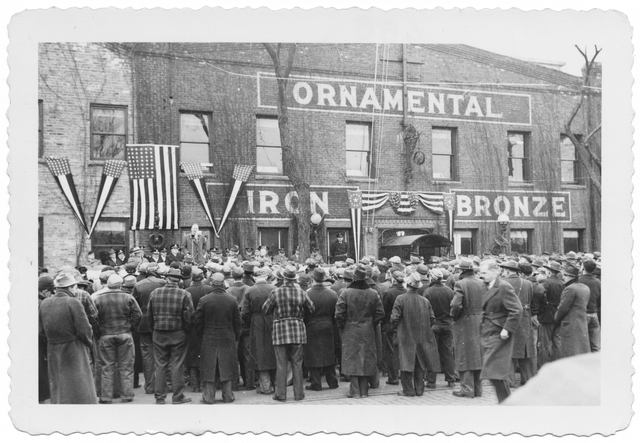

In 1907, Robinson built the first of many buildings for Flour City Ornamental Iron Works. Flour City began as a blacksmith shop and, with Robinson as a contractor on most of the buildings, grew into a campus of foundries and workshops. Supplying metalwork for landmark buildings locally and around the world. By WWI, it was the largest business of its kind in the United States.

Flour City gradually diversified (Alumacraft began here), and its operations were eventually scattered across the country. The existing building from the old Flour City Iron Works can be seen today, where 27th Avenue crosses the Greenway. It is charmingly decked in foliage and is now called the Ivy Building. Albeit on a smaller scale, this space still perpetuates craft traditions and still celebrates makers by housing studios and galleries.

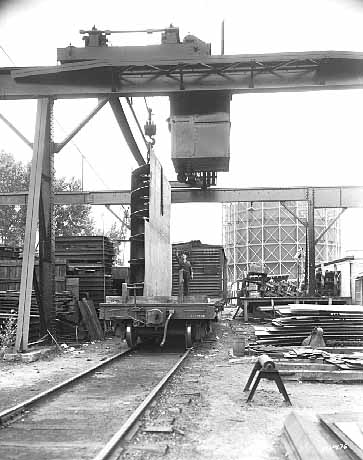

By 1910, having spent the last few years building out the Flour City campus, Robinson was the natural choice to build another, very similar, metalworking factory: Crown Iron Works.

Crown was located along one of the multitudinous rail sidings of northeast Minneapolis, near the intersection of Central Avenue and Broadway Street. Crown began life in the 1870s, servicing the mills along St. Anthony Falls and fulfilling the various and extensive ironworking needs of Minneapolis’s millers. By the 1900s, Crown diversified and was providing ornamental iron for the construction industry. The plant that Robinson built in 1910 was part of further expansion and diversification efforts.

In the 1980s, Crown was one of countless US firms that were driven out of the steel business by intense foreign competition. Whether or not it is mere coincidence, Crown returned to a business model that is reminiscent of its origins. Still calling itself Crown, and still based in Minnesota, Crown is now a process engineering company with a focus on the edible oils industry. They build and maintain facilities that extract oil from plants. Facilities that, in the 1800s, might have been called mills. The factory that Robinson built in 1910 has been charmingly repurposed. It is now used by Bauhaus Brew Labs and other local businesses.

Both Crown and Flour City are emblematic of an era when heavy industry dominated the Minneapolis economy. Both companies began as blacksmithing shops. They both grew into large manufacturers with national markets.

In 1917, Robinson rounded out his decade of heavy industry building with the Iron Store. Unlike the Flour City and Crown, the Iron Store, in the warehouse district just north of downtown, wasn’t a factory. It was more of a warehouse and as the name suggests, a store. It was, however, a special sort of store that can no longer be found in Minneapolis. It was once the nation’s largest supplier of heavy equipment. If you needed an axel for a carriage, the Iron Store would be a good place to look. If you needed the tooling machines necessary to make carriage axles, the Iron Store would be a great place to look.

The Minneapolis Iron Store began as a St. Paul hardware store in 1851. Selling horseshoes and other necessary metalwork at the fast-growing steamboat landing set a foundation for a business that eventually sold everything from small hand tools to large factory equipment all over the Midwest. After consolidations and mergers, the business moved to the railroad and jobbing center north of downtown Minneapolis. Now part of the Minneapolis Warehouse Historic District and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Minneapolis Iron Store building exists today. However, researcher and historian, Penny Peterson, aptly states, the building suffered some “insensitive remodeling.”

The building was recently converted into lofts, which, it appears, improved what was previously done to the window openings. However, the cornice is forever lost.

Having been built to withstand the rigors of heavy industry, the projects that Robinson worked on between 1907 and 1917 are still part of our built environment, monuments to the constancy of change.

CATEGORY: History