March Friday History: Elizabeth Close and Metropolitan Medical Center

Kraus-Anderson has been building hospitals for more than a century, but in the 1960s KA took an unusually active role in the history of the Minnesota healthcare industry when it facilitated the merger of two historically significant institutions in the Eliot Park neighborhood of Minneapolis: Swedish, and St. Barnabas Hospitals.

Building the Metropolitan Medical Center was a challenging, profoundly complex, multi-year construction project, which makes it a noteworthy chapter in the Kraus-Anderson story, but, in the long run, it might be the collaboration with pioneering architect Elizabeth Close that makes this project memorable.

Elizabeth Scheu Close

Coming to Minnesota in 1936 with a degree from MIT, Elizabeth Scheu Close was one of the first women in the state to practice architecture professionally, but more to the point, as her biographer Jane King Hession points out: “Close was the first European-born practitioner of the international style to practice in the state.”

Born in 1912 Vienna, and raised in a house designed by Adolf Loos, Elizabeth Close (born Elizabeth Scheu) left Austria in 1932 to attend college and graduate school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then as now a top educator of architects. Precious few women worked as architects in the 1930s, but Elizabeth Close (known as Lisl by both friends and admirers) possessed talents as a designer that were undeniable.

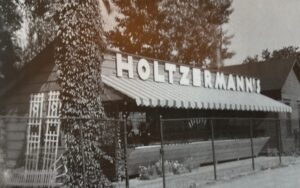

1936 Lisl moved to Minneapolis to join her future husband at the firm of Magney and Tusler, but two years later she and Winston Close both married and formed a new architecture practice. Close Associates always specialized in residential design, but commercial projects have been sprinkled into the Close portfolio from the firm’s earliest days. One of their first commissions was this storefront.

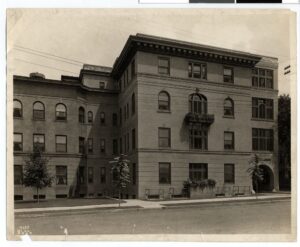

In 1953 the Closes designed and built this understated HQ building on the corner of 31st Avenue and Franklin that Close and Associates still call home.

The Metropolitan Medical Center

The Elliot Park neighborhood has been a healthcare hub since the early days of Minneapolis, but the middle of the 20th century brought changes to the healthcare industry. Asbury Methodist, which faced Elliot Park since the 1800s, built an ambitious new campus in St. Louis Park in 1959. Soon after that, the two remaining hospitals in the neighborhood began planning a merger. The resulting entity (countless construction projects later) was briefly known as the Metropolitan Medical Center but is now called Hennepin Health.

Metropolitan Medical Center Office Building

Kraus-Anderson was more than just a construction manager on the Metropolitan Medical Center. Seeing the need for auxiliary space for medical professionals to ply their trade, KA developed the Metropolitan Medical Center Office building. An innovative and unique leasing agreement gave the doctors who operated in this building an option to purchase the facilities at the original cost of construction after seven years.

Kraus-Anderson tapped Close and Associates to design the new medical office building, a rare example of an office tower in the Close portfolio, but KA had been working with Elizabeth Close on the hospital merger, and her modernist/internationalist style of design was likely deemed a natural fit for the medical campus’s vertical element.

Elizabeth Close and the Medical Center

Elizabeth Close began designing medical building early in her career. In 1940 Lisl gained attention for the stark, uncompromising choices she made in the design of the Interstate Clinic in Red Wing Minnesota.

Fast forward to the 1960s, and Close is the go-to architect for St. Barnabas at the time of its merger with Swedish Hospital, who had their own go-to designer. This comes from the book Elizabeth Scheu Close: A Life in Modern Architecure: “The two boards couldn’t decide whether to hire Tom Horty, who was doing the Swedish Hospital, or hire me, who was doing St. Barnabas” …. So they came to us and asked, ‘could you work together?’ We said sure, no problem.”

Close worked on patient care areas while Tom Horty focused on labs and surgical spaces. One of the pioneering aspects of this project was Elizabeth Close’s decision to implement the Friesen system of patient care. Close’s biographer Jane King Hession describes it better than I can: “The fundamental idea behind Friesen’s system was the availability of a nurse to the patient at all times. To facilitate this, he advocated a supply distribution system that made everything a patient needed accessible from a single cabinet in or near the patient’s room… This rethinking of the nurse / patient relationship put nurse servers in the hallways, which decentralized the staff so that the staff could be in the room and in audio contact with the nursing center. That was revolutionary.”

In 2011 Elizabeth Scheu Close passed away in her adopted home of Minneapolis. With too many accomplishments to briefly summarize, her son Roy Close described her simply, poignantly, as “a diminutive woman in a hardhat.”

CATEGORY: History