October’s History Friday: Harry Wild Jones

By Matt Goff, Kraus-Anderson Historian/Archivist

It is commonly said, but made no less truthful by repetition, that the construction business is about relationships. The all-important relationship between builder and client, as well as the web of relationships among architects, engineers, subcontractors, and more, are required to complete a building project. One of the most important relationships in the early history of Kraus-Anderson was the one between J.L. Robinson, the founder of Kraus-Anderson, and architect Harry Wild Jones.

Jones Born into Opportune Times

Born in 1859, Jones was part of a generation of architects who benefited from a well-timed birth. With careers that overlapped with the building of so many new cities and towns, this generation came into an opportunity to have their work admired for ages. This is especially true if, like Harry Jones, an architect has the talent and temperament to create monumental buildings.

With the right amount of flamboyance and exacting attention to detail, Jones had a knack for creating spaces that were otherworldly without being ostentatious. He specialized in church buildings. Minneapolis, where Jones spent most of his career, is fortunate to have several examples of his sacred architecture. The midwest, especially greater Minnesota, is dotted with his churches.

The Beginning of the Jones-Robinson Partnership

Robinson and Jones first worked together in 1902. J.L. Robinson was enjoying his first major career success (the 1901 Dayton’s building), and Jones had his hands full, designing buildings for the rapidly-forming Minneapolis park system. Robinson was chosen to build a wooden pavilion that Jones designed for Minnehaha Park. Although this pavilion was almost immediately destroyed by fire, Robinson also built its replacement (this time made of concrete) in 1905. The 1905 “refractory” building can still be seen today in Minnehaha Park. It houses the Sea Salt restaurant.

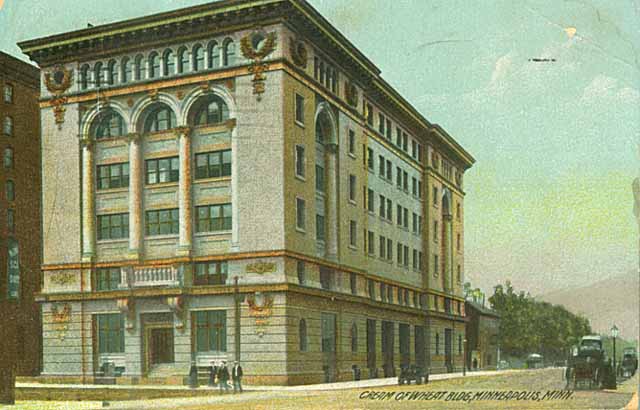

In the year between the two Minnehaha Park buildings, Jones designed (he won a competition to become the architect!) and Robinson built a factory / headquarters for Cream of Wheat. It was located in the heart of downtown Minneapolis, on the corner of 5th street and 1st Avenue North. While it was atypical to locate a factory in the central business district in 1904, this was not a common factory. With its classical revival exterior, the building was ornate, even when compared to the architectural landmarks found nearby.

The resulting project gained national renown. Not only was this a beautiful place to turn wheat middlings into hot cereal, but there was also an Italian garden along the east side of the building and another on the rooftop for the enjoyment of the employees. After twenty years, the Cream of Wheat operation outgrew its downtown location. Jones’ masterpiece suffered the indignity of being used as a parking ramp before eventually being torn down in 1939.

Minneapolis Scottish Rite Temple

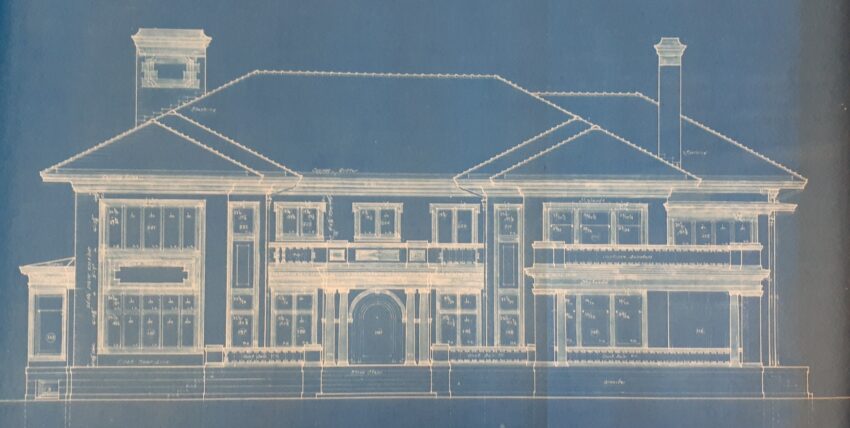

The next landmark that Jones and Robinson collaborated on enjoyed a more fortunate career. In fact, it can still be seen today on the corner of Dupont and Franklin Avenues, in the uptown neighborhood of Minneapolis. For more than one hundred years, this structure has been home to the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite Masons of the Valley of Minneapolis in the Orient of Minnesota.

What Robinson built over the years 1906 and 1908, however, was the Fowler Methodist Episcopal Church. The congregation for which the church was originally built used the building for a mere decade. They sold the structure to the Scottish Rite masons in 1915 when the Fowler congregation merged with the Hennepin Avenue Methodist Church. The Scottish Rite temple hosted the largest funeral ever to take place in Minneapolis after the famed pilot Charles “Speed” Holman crashed his plane in 1931. In 1974, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Projects, Both Big and Small

Robinson and Jones worked together on more than large, monumental projects. There are countless historic permit records for renovations, additions, and small residential buildings in which both of their names are listed.

An example that suggests a personal, as well as a professional connection, can be found at 2505 Pleasant Avenue. In 1908, fresh off the Fowler Methodist project, Jones designed the house that Robinson built next door to his family home.

The last major project that Robinson and Jones collaborated on combined the monumental with the residential. Ten years after the Cream of Wheat building was completed, the pair came back together. Jones designed and Robinson built two residences for the Mapes family, the owners of the Cream of Wheat company. Even by Lake of the Isles mansions’ standards, these residences are unique. Emery Mapes had an Italianate mini-palace built for his own enjoyment. Right next door is the craftsman masterpiece, built for his son Frank Mapes. Made of steel and reinforced concrete, these mansions still grace the Lake of the Isles shore with an abundance of original details in place.

Although the Mapes houses were the last major projects for Jones and Robinson, the two continued to work together occasionally until the end of their careers— notably, on renovations and additions for Nicollet Park, home to the Minneapolis Millers. Robinson retired in 1930 and, working seemingly right up to the end of his life, Jones passed away in 1935.

CATEGORY: History