The Origins of Kraus-Anderson

It is sometimes difficult to give a precise point of origin for a business. The name Kraus-Anderson emerged in the 1930s, but, since Amos Andersen and Mathew Kraus were employees of the prolific builder J.L. Robinson, Kraus-Anderson traces its origins to the beginning of Robinson’s career. The earliest evidence (yet discovered) of Robinson working on a commercial building comes from the year 1897, so this is the accepted birth year of Kraus-Anderson. With another landmark year (125 year anniversary) approaching, it might be worthwhile to examine some alternative origin stories.

A House on Elliot Avenue

The first building that J.L. Robinson built (or at least the first building for which there are existing records) was a barn on 27th Street, near 3rd Ave. Assuming this humble structure survived into the mid-20th century, it was one of the countless structures torn down to make way for the I-35 freeway. Robinson again appears in the historic Minneapolis building permits in 1889, when he built a house for himself and his family on Elliot Avenue near 35th Street. This was a savvy move by the young construction entrepreneur, because the very next year the city of Minneapolis finally succeeded in acquiring the property surrounding nearby Powderhorn Lake and began the process of creating Powderhorn Park.

When Robinson built his house on Elliot Avenue, it was in a sparsely populated area. Between the amenity of the nearby park, and the Chicago Avenue streetcar, only a block away, the Robinsons lived in a bustling neighborhood by the turn of the century. In 1902, after enjoying some success in business, J.L. Robinson felt he had outgrown his house on Elliot Avenue. He built a new one on the corner of Pleasant Avenue and 25th Street. A 1912 fire insurance map indicates that the house on 25th and Pleasant was a bit larger. It also included a car garage, suggesting that the Robinson’s were early adaptors to the automobile age, no longer reliant on the streetcar. Ironically, the newer and upgraded house that Robinson built in 1902 was torn down and replaced by an apartment building, but the more modest house in the Powderhorn Park neighborhood survives to this day

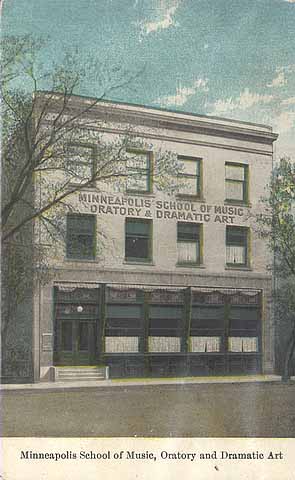

Johnson Music Hall

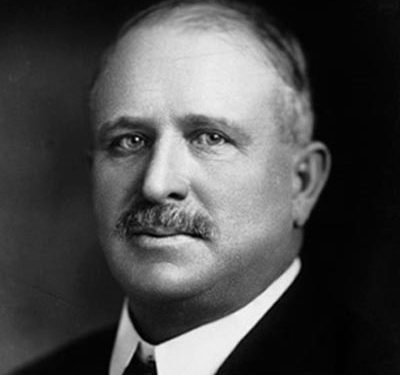

An argument could be made that the Johnson Music Hall, built in the year 1900 on 8th Street between Hennepin and Nicollet Avenues, is the starting point for the history of Kraus-Anderson. This is the earliest commercial building entirely constructed by J.L. Robinson. Previous to the music hall, Robinson’s portfolio was limited to houses, sheds, and barns. Although the Johnson Music Hall, a three-story brick building that has long since given way to the wrecking ball, can be seen as a modest beginning, this small music conservatory played an outsized role in the cultural history of Minneapolis.

The heyday of Minneapolis music invokes, to most of the city’s residents, First Ave in the 1980s, Prince, maybe the Ramones, but there is a distant prequel to all of this in late 1800s, when Minneapolis was choked with talented musicians, composers, and music teachers, most of them recent immigrants from Europe. Gustavus Johnson, born in England, but raised in Stockholm, was prominent among them. Johnson was an accomplished composer and pianist, but he was best known by his contemporaries as a strong and innovative music teacher. By 1900 his school had grown large enough to require a music hall of its own.

Although not an ostentatious building, it was apparently a stretch for Gustavus Johnson. He declared bankruptcy in 1907. The Johnson Music Hall was taken over by group of Minneapolis businessmen, and continued on as the Minneapolis School of Music, Oratory, and Dramatic Art, which would eventually become the Minneapolis College of Music. Gustavus Johnson’s work as a teacher and musician was only slightly impaired by the loss of his hall. He continued teaching elsewhere, and became one of the founding members of the Evergreen Club, which flourishes to this day as a social and promotional club of “hardworking musicians, music marketers, and music teachers.”

Mahala Fiske House

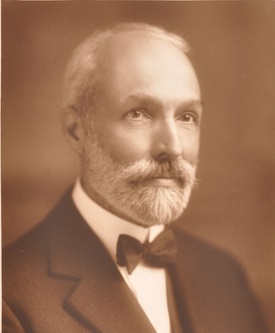

In September of the year 1900, J.L. Robinson got a permit to build a “women’s club” at 819 2nd Ave S. Called the Mahala Fiske Pillsbury House, this relatively modest structure has an outsized importance for Kraus-Anderson: built in the same Summer as Johnson’s Music Hall, it was one of Robinson’s first major efforts. More importantly, it was Robinson’s first job for a major client: The Pillsbury family.

The building also holds an outsized place in the history of Minneapolis, which, in 1900, was a city beset with demographic challenges. Half of the female workforce, about 9,000, were living as single women. Similar things were happening across the country, as recent immigrants were joining rural transplants to form a population deluge into U.S. cities. Several organizations were rising to meet the challenges and perceived threats of so many young people living apart from family and familiar institutions.

In the second half of the 1800s, Minnesota attracted people from all over the world with its agricultural opportunities, and this settlement pattern (among other factors) left a larger proportion of women seeking opportunities in the Twin Cities than in comparable cities nationwide. The Minneapolis Women’s Christian Association (WCA) maintained houses all over the metro area where single women could live safe and connected while they independently pursue a living.

In one of the last acts of a life famous for philanthropy, John Pillsbury had this house built, and he named it for his wife Mahala. By the middle of the 20th century, there were few “women’s houses” left in the Twin Cities, but the Pillsbury house was particularly well-placed for its mission, and in 1955 the old Mahala Fiske Pillsbury House was torn down, not to make way for new development, but to rebuild the house on a larger scale (and in a more midcentury style). Now called the Exodus Residence, the purpose of the building has shifted only slightly to be “health supported housing for men and women.”

Dayton’s Store

The summer of 1900 was an important time for J.L. Robinson’s career as a builder, but the next year has to be considered a miracle year, the one that would make his reputation, because in 1901 Robinson began work on a store for George Dayton that remains a major Minneapolis landmark.

The great retail empire that the Dayton family built didn’t begin with a single store so much as it began with a single building, and that building was constructed by J.L. Robinson. When George Dayton came to Minneapolis, he didn’t intend to make a fortune in retail. He came to Minneapolis to grow his existing fortune by investing in real estate. The Goodfellow’s store is the tenant that Dayton happened to find for his ambitious development project at 700 Nicollet, but he soon owned the store as well as the building that housed it.

As he was a relatively inexperienced builder in 1902, it’s hard to know exactly why J.L. Robinson was chosen to build George Dayton’s landmark building. Based on what we know of his subsequent career, it seems that Robinson had a knack for instilling confidence and building relationships. The job that Robinson did was worthy of the trust placed in him. Now known as the Dayton’s Project, the building Robinson completed in 1902 continues to be crucial to the infrastructure of Minneapolis, while adding beauty to the downtown landscape. Further success was not guaranteed to Robinson after the Dayton’s building, but, after the Dayton’s building, the story is about turning points, not points of origin.

CATEGORY: History